There is no try: Just do

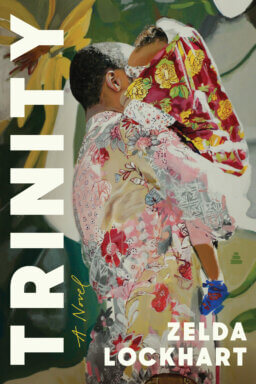

“Trinity” by Zelda Lockhart

c.2023,

Amistad

$27.99

272 pages

If at first, you don’t succeed…

The old saying recommends trying three times, but that can be nothing but frustration: if it ain’t working, what says it might work later? Try, try again is fruitless but then… there are those days when a third attempt, or a fourth or a fifth is all it takes to get things done. As in the new book, “Trinity” by Zelda Lockhart, the third time’s indeed the charm.

Bennie Lee was somewhere around ten or eleven years old when his mother, Lottie, left Bennie and his toddler brother, Lenard, in the care of their father, Big Deddy. That care, though, was given through fists and slaps and overwork and denial.

Lottie always said she wanted to go to St. Louis and she’d take her boys with her but Bennie knew she was at a bar a few miles away, selling her body to men. He tried to bring her home, but she acted like she didn’t know him. When she came back to their Mississippi farm on her own, he shot her dead, chasing away the girl-spirit that waited in Lottie’s womb.

And then Bennie bolted.

He left Mississippi, joined the Marines in Korea and when he came home, wounded, he brought alcoholism with him. Still, he stayed sober enough to meet Rebecca, who dreamed of marrying a Marine and she and Bennie conceived a child, so she got her wish.

They named that baby Bennie Jr., and they called him BJ. He would have had a sister but when Rebecca Lee was four months pregnant with their second child, Bennie shot her and then himself, and the girl-spirit was chased away again.

Lenard Lee was glad to take his nephew in after the murder-suicide of the boy’s parents. Six-year-old BJ grew up with every opportunity America in the 1950s could offer and when he was old enough, he fought in Vietnam like many young men his age.

Also, like many young men his age, he fell in love with the girl next door when he came home.

When she told BJ that he was going to be a father, the girl-spirit rejoiced…

Despite the wince-worthy violence inside this story and a few pages of surprising explicitness, “Trinity” is really a very pretty book. The imagery inside is dusty and lush, and it’s helped along with gorgeous turns of phrase and occasional sly sarcasm, both of which poke the imagination: you can almost feel the Mississippi heat, the suck of mud on a creek bank, and kudzu choking your ankles. Beginning each chapter and appearing elsewhere when needed, its spirituality feels like a bucket of cool water on a hot day; the ancestor love that author Zelda Lockhart allows for her characters fits perfectly into the rest of what happens.

Because of its flowing language and metaphors, this book may take some patience to embrace and its spirituality isn’t for everyone. Still, if this doesn’t sound like your kind of book, pick up “Trinity” anyhow, and try, try again.